By Yitbarek Woldetensay and Chelsie Kuhn

Background

Local ownership and organizational learning have become integral to many international programs that engage in capacity development. However, many local organizations still need greater capacity to assume this leadership role. Hence, many international programs want to assess organizations’ capacity before and after their capacity-building interventions to identify capacity-building priorities and measure organizational capacity change over time. An Organizational Capacity Assessment (OCA) is an assessment approach that provides a general overview of organizational capacity, often through a participatory process. We plan to describe OCA and OCA tools in a two-blog series. In this first blog, we will describe an OCA, why implementers should conduct an OCA, what preparation is required before OCAs can be used, and how to prepare the OCA tool. In our second blog, we will cover how to facilitate OCA workshops and how implementers can use the information resulting from this assessment.

What is an OCA? When would organizations use it?

The OCA is a structured tool for a facilitated self-assessment of an organization’s capacity followed by action planning for capacity improvements. One unique feature of this approach is that it is self-scored, not interviewer or researcher-scored. The OCA format helps the organization reflect on its processes and functions and score itself against benchmarks for different subdomains of skill or capacity. The organization’s participants discuss institutional abilities, systems, procedures, and policies in various capacity areas. Then, they agree on scores based on statements that reflect different capacity levels. The scores are supported by justifications, explanations, and supporting documentation for each item the organization’s participants provided.

Organizations may use an OCA when they are looking to understand better where their current skills stand and if there are any gaps. The process can promote information sharing, a healthy internal dialogue, and consensus building by including representatives from various units and levels of the organization. It can also help build relationships and trust within and between the organization. However, an OCA is not an audit, facilitator-scored, or interview, and so the scores are not “corrected” by the external facilitators. The OCA is not intended as an external evaluation of organizational, program, team, or staff performance. The OCA is also not intended to be a comparison between non-related organizations, as, without agreed-upon definitions, the results would be too subjective for direct comparison.

Why conduct an Organizational Capacity Assessment?

There are several reasons why implementers need to conduct an OCA. This tool provides a structured reflection by encouraging the participants to think deeply and reflect on their organization’s internal operations. By bringing different people together and enabling each group to assess the organization from their perspective, users can learn how different stakeholders value, measure, and experience various aspects of an organization’s capacity. The tool also allows users to discover for themselves what skills and capabilities are possible and are needed in the future to strengthen the functioning of their organization.

The OCA tool breaks organizational capacity into its various components and then presents a range of verifiable indicators. This simplifies identifying and agreeing on specific targets to be achieved within a certain timeframe. Using the same criteria to measure capacity over time, it is possible to monitor the areas where capacity has been enhanced and discover areas where it may have inadvertently declined. If targets have been set related to capacities, then this tool can measure how the organization is progressing toward those targets. It is also possible to compare baseline ratings with the level of capacity measured after a certain period. This will help identify capacity changes over time and help implementers deduce which interventions may have contributed.

Moreover, the OCA can establish a benchmark for exit strategies. Exit strategies often include capacity benchmarks that both parties try to achieve to ensure the sustainability of the partner after the end of a partnership or program. This tool allows concrete benchmarks to be established and progress towards these monitored.

What is it like to facilitate an OCA?

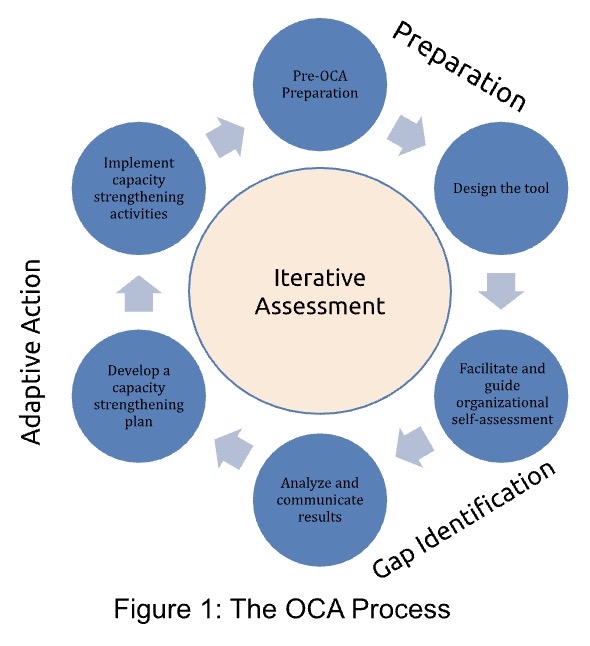

The OCA process has three major phases: tool preparation, gap identification, and adaptive action planning and implementation. Of the three phases, the preparation phase needs a longer duration as it involves convincing the organization’s senior management of the advantages of conducting OCA and securing their commitment; contextualization of the OCA tool to be used; selection of participants; and planning for budgeting, staffing, and other resources. Gap identification is composed of collecting the information, processing the findings, and preparing recommendations. Then adaptive action planning and implementation take that information to create a change plan.

How do you prepare for an OCA?

Ensuring senior management commitment, selecting participants, planning, securing resources, including facilitators, and developing the OCA tool are the main areas one must prepare for before conducting an OCA facilitation workshop.

Ensure senior management commitment: An OCA might not be very productive if the organization is an unwilling participant as they are less likely to implement any resulting adaptations. The organization must be convinced that conducting OCA has a real advantage. The organization, especially the senior management, must be committed to going through the process and following its recommendations. The facilitator should clarify the goals, procedures, and expectations early to gain buy-in.

Identify Participants: Determining who should participate in the assessment to represent the diverse opinions from relevant departments or offices is crucial in the OCA process. The ideal number of participants is 8 – 15 people per organization. If we involve a bigger group, the data collection process will take longer and might be boring or taxing for the participants. On average, an OCA process can take five to eight hours to implement: the bigger the group, the slower the process, as it takes time for each person to rate capacities and provide rationale. If the organization is small, conducting the OCA in a plenary session with key management and staff discussing all the capacity areas is best. For large organizations, it may be helpful to have different teams of participants for some or all sections of the OCA. Relying on concurrent sub-groups can be more efficient so that the OCA can be done faster. Each team should include one or more members of senior management to ensure commitment to taking identified recommendations into action. So, the ideal size of the discussion groups will vary with the size of the organization, individual and cultural factors, the facilitators’ skills, and whether the group is covering the whole OCA or only a part of it.

Plan Staff and Budget: The resources required to ensure a robust OCA process are staff time and necessary workshop costs. Any OCA requires at least one in-person workshop with each participating organization and at least one well-prepared OCA facilitator who knows the OCA process. If being facilitated externally, it is usually more cost-effective to send facilitators to the organization’s location and transfer the ownership and responsibility to the organization for leading the OCA process from the very beginning. This helps ensure participant buy-in, reducing the sense that the OCA is an audit and leveraging the organization’s existing relationships.

Choose and adapt an OCA tool: Today, many different OCA tools are used and constantly developed by various organizations. Though the tools have many similarities in core composition and underlying principles, they also have specific differences depending on the type of organization and scope of assessment. Thus, one can skip drafting an OCA tool from scratch but can use the existing tools and adapt those for the intended use by adding and removing domains or subdomains and specific items accordingly. Choosing the right OCA tool depends on understanding the purpose of the assessment, the organization’s size and structure, its phase in the organizational life cycle, and its current capacity to administer and use the findings from the assessment. For example, below are the steps that the Headlight team followed to develop an OCA for a USAID-funded project. The OCA tool was prepared to identify targeted capacities to strengthen through the program intervention and, in the future, understand how capacity growth has improved disaster response efforts.

- Review existing OCA tools and identify potential domains and subdomains that fit: First, we reviewed as many existing OCA tools as possible, focusing on the domains and subdomains that match the project’s intervention areas. This way, we identified a list of OCA tools where the project interventions might influence domains and subdomains. Accordingly, we selected the USAID OCA tool as the best starting point. We presented it to the project team to further identify and contextualize which domains and subdomains their interventions have the potential to influence.

- Match the identified domains/subdomains to the project intervention areas: We invited the project team for a three-hour workshop to execute the matching exercise. We prepared a MURAL board populated with the USAID OCA domains and subdomains. Under each domain and subdomain, we provide space for the project team to write a list of their intervention that has the potential to change the respective capacity domains and subdomains positively. During the workshop, the program team listed interventions that may influence the capacity domains and subdomains.

- Remove domains and subdomains for which no interventions were matched: After all of the activity’s work was listed, we removed domains and subdomains for which no interventions were matched. These are often domains and subdomains that the proposed interventions may not directly or indirectly change. One example of this was the team removed subdomains under the “Program Management” domain, including donor compliance, sub-grant management, technical reporting, and referral, as their intervention has no potential impact on these capacity components.

- Identify interventions that didn’t match with the domains and/or subdomains: Then, the project team identified a list of interventions that did not match any of the domains or subdomains, categorized them into additional new domains/subdomains, and named them. Here the project team added domains like “Disaster Response Capacity” and specific subdomains which the project has the potential to impact.

- Prioritize domains and subdomains: Once the domains and subdomains were selected and new ones were added, we prioritized domains and subdomains based on feasibility and impact. This helped to understand which domains were ready to be worked on and what would bring the most value-add for improving capacities.

Develop representative statements (items): Finally, the project team identified a potential list of representative statements for each sub-domain. For example, under the knowledge management subdomain, our colleagues used representative statements such as “Our organization regularly documents lessons learned and best practices.” These representative statements are the final items in the OCA tool to identify the capacity gaps. Each representative statement is followed by qualitative questions (How did you come to this rating? Are there examples?) to understand why the participants score the statement that way. This will allow hearing stories of what works well and different perspectives on what could be improved. So, both the quantitative and qualitative pieces of the information could be collected simultaneously.

Closing

In general, the OCA is a facilitated self-assessment of an organization’s capacity and helps to identify organizational strengths, weaknesses, successes, and areas for improvement. Good preparation: ensuring senior management commitment, identifying appropriate and representative participants, and preparing a customized tool, is crucial in the OCA process. We hope this blog helps you better understand what an OCA is, the benefits of implementation, and how to prepare for facilitating an assessment. In the next blog, we will explain how to facilitate an OCA workshop and how to use the resulting information. Stay tuned!

References

1. C. Mike Daniels (2016). Organizational Capacity Assessment Tool (OCAT) User Guide.

2. AmeriCorps. (2017). Organizational Capacity Assessment Tool.

3. John Snow, Inc. (2012). Organizational Capacity Assessment Tool (OCAT): Participant’s copy

4. John Snow, Inc. (2012). Organizational Capacity Assessment Tool (OCAT): Facilitator’s copy

6. Mwiya Mundia (2009). Organizational Capacity Assessment: An introduction to a tool.

Comments

no comments found.